Press

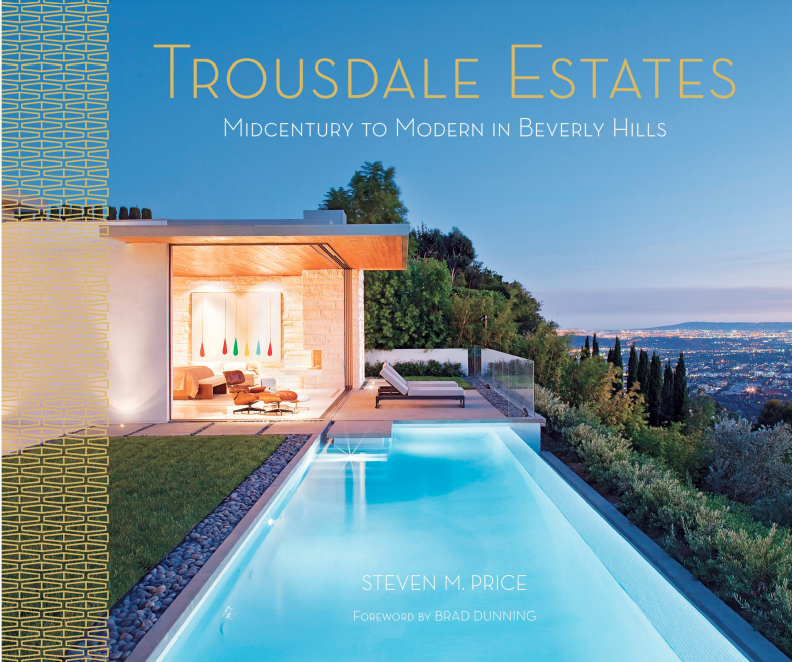

Trousdale Estates

Atomic Ranch Spring

Pro Portfolio: Cory Buckner’s Brentwood Modern

The Korman Residence by Cory Buckner Architects

AIA Home Tour Q&A

Lady of the Canyon

Korman Residence

Trousdale Estates

Trousdale Estates

Written by Steven M. Price

In contrast to the elongated, horizontal profile of his Model House No. 2, with his second model design, architect A. Quincy Jones literally “raised the “roof – a dramatic sheltering gable becomes the defining feature of this cathedral-like structure. Read more

Atomic Ranch Spring

An architect, whether for the landscape or your home, knows a lot more than you do and can save you a lot of pain and money—like when you find out that your pool would be too close to your neighbor’s property line, or that the new drainage now leaves your driveway a swamp after a big rain. Good architects also have a tried-and-true work force, in contrast to hiring an independent pool guy, a hardscape guy and plant-material guy.

An architect, whether for the landscape or your home, knows a lot more than you do and can save you a lot of pain and money—like when you find out that your pool would be too close to your neighbor’s property line, or that the new drainage now leaves your driveway a swamp after a big rain. Good architects also have a tried-and-true work force, in contrast to hiring an independent pool guy, a hardscape guy and plant-material guy.

Another realization was that the original 1959 electrical panel we nostalgically left in place might be a bit outdated. When we tried to use both a toaster and a new deep-fat fryer at the same time, it blew out all the fuses in the front of the house. The Magic Chef appliances from the 1980s were also dying, and the cheap maple veneer cabinets were peeling badly. So we started interviewing—interior designers at first. They clearly did not get it.

Korman Residence

Wood Design & Building

Printed Issue: Fall, 2008

Modern remodel leverages techniques and treatments appropriate for a house tucked into a wooded California canyon.

Cory Buckner, Architect

In 2005, Dr. Jeremy and Ann Korman sought to remodel their Brentwood home. With two daughters and a French bulldog, they had long outgrown their 1,700-sq.ft. ranch house built in the 1950s. They longed for contemporary, comfortable space for their family.

The client was drawn to the postwar post and beam architecture of the modernist era. The house is located just outside of Crestwood Hills, formerly called the Mutual Housing Association tract, designed by A. Quincy Jones, Whitney R. Smith, and Edgardo Contini in the late 1940s.

The client was drawn to the postwar post and beam architecture of the modernist era. The house is located just outside of Crestwood Hills, formerly called the Mutual Housing Association tract, designed by A. Quincy Jones, Whitney R. Smith, and Edgardo Contini in the late 1940s.

The program for the project included a second storey addition to house a master suite, a home office and a painting studio. Situated at the bottom of a canyon, the entrance to the original house was 66 steps from the street to the front door. The new design incorporated a bridge to an entrance at the second floor addition reducing the steps to 44. The former master bedroom on the lower level became one daughter’s room and two small bedrooms at the rear of the house were combined to make a suite for the other daughter.

The entire house was impacted by the remodel with most of the house being demolished. The former master suite, kitchen and dining roof structure remained intact but many interior walls were demolished or reconfigured.

A butterfly roof structure was designed for the second story addition in order to capture light from high clerestory windows that reach up to the ceiling. Some of the window configurations on the original house incorporated posts and worked well with the second story addition designed as an exposed post and beam structure. Skylights were added in the kitchen and over the fireplace, which in addition to adding light in the living room accents an articulated tiled fireplace mass. All bedrooms face patios or decks with sliding glass doors that dissolve the boundary of indoor and outdoor space.

The second-story addition and 719-sq.ft. addition were complete in October 2006. The finish material palette was kept appropriate for a house tucked into a wooded canyon. The existing house was finished in rough sawn board-and batten with a composition shingle roof. The new house is clad in new growth cedar tongue and groove siding with a roof covered in slate green gravel. Douglas fir flooring and cabinets were used throughout the project. The significant use of wood as a structural and finishing product has given the Kormans a residence that reflects its wooden surroundings.

Architect: Corry Buckner, Los Angeles, CA

Client: Dr. Jeremy and Ann Korman, Los Angeles, CA

Structural Engineer: Scott Christiansen, Los Angeles, CA

Soils Engineer: Mark Kruger, Geosystems, Los Angeles, CA

General Contractor: David Stumfall & Randy Hayden, Supervisor, Palisades Construction, Los Angeles, CA

Interior Designer: Owner and Architect

Photographer: Sunshine Divis, Jonnu Singleton

Home Tours Q&A with Architect: Cory Buckner, AIA

AIA | Los Angeles

Click here to read original story.

We continue our AIA Los Angeles Spring 2011 Home Tours architect interviews with Cory Buckner, AIA, designer of the Brentwood Residence. In this edition, she answers questions regarding the home’s floorplan and offers an interesting take on the historical difference between East and West of Los Angeles. Read on to find out more.

We continue our AIA Los Angeles Spring 2011 Home Tours architect interviews with Cory Buckner, AIA, designer of the Brentwood Residence. In this edition, she answers questions regarding the home’s floorplan and offers an interesting take on the historical difference between East and West of Los Angeles. Read on to find out more.

1. Did the environment or culture where the home was built influence the design?

The house is situated within a well-known architectural community that was originally designed by A. Quincy Jones, Whitney R. Smith, and Edgardo Contini in the late 40s. I wrote a book on Jones and am very familiar with the modernist houses that were once called Mutual Housing Association. My husband, architect Nick Roberts, and I live in one of the original houses within walking distance of the project. The primary objective was to design a residence that would fit into the community of modest-scaled homes. To minimize the bulk of the project, the house was placed back from the street and presents an elevation that is only 8 ft. high from the street level. Stepping down the hillside, the house gives the impression that it is smaller than it is.

The design of the house is very influenced by the neighboring modernist homes. The use of butterfly roofs for the house and the separate artist’s studio at the rear of the property allowed for generous clerestory windows, which in turn created a floating roof. In addition to the clerestories, all of the MHA houses featured plentiful glass, which celebrated the connection of indoor and outdoor space. Exposed materials such as concrete block, redwood siding, and plywood were used throughout the original MHA houses; the Brentwood House featured cedar siding, glass walls and exposed concrete that blend well with its neighbors.

2. How do you see the project now that it is finished?

I am particularly proud of the Brentwood Residence. Crestwood Hills in Brentwood is a postwar modernist community where I currently live and have been very active in preservation, working on over a dozen architectural projects in the community. A primary objective of this project was to create a design that blends and enhances the character of the community; the Brentwood Residence carries on the modernist legacy of the neighborhood.

Successful architectural projects require a team of people to carry through a vision. They are particularly dependent on a client that is not only supportive of the design, but willing to put in time and money to see the structure built to the highest standards possible. I see the project as a collaboration with my clients, with their sophisticated sense of design. I also credit the superb work of the flexible and patient David Stumfall and Randy Hayden of Palisades Construction.

3. What is your favorite feature of the home?

It is a pleasure to watch my clients and their two daughters enjoy their new home; each with their own personal space but sharing an open plan kitchen, living, and dining area. The floor plan is not technically considered a feature, but it is the element that makes the house work as well as it does; it is my favorite feature of the house.

4. What are your thoughts on the difference between the eastern region and the western region of the 405 freeway?

The relationship between West Los Angeles and downtown has mutated over the years: in the early twentieth-century the beach resorts of Santa Monica and Venice were a short ride away from Los Angeles on the Red Car, but separated from the city by undeveloped farmland.

Attracted by the weather, plentiful employment in the aircraft industry, and the overall beauty of the Los Angeles area, World War II veterans came in droves, creating a dire need for housing. The optimistic flush and healthy employment of those early postwar years fueled the American dream of home ownership, with one and often two cars in the garage. With the support of the Federal Highway Administration’s freeway program, it created an Arcadian paradise far away from the city center, pushing into the San Fernando Valley and creating Westside communities such as Brentwood, Palms, and Mar Vista.

The rush to the suburbs of the 1950’s and 60’s had its dark side: the abandonment of traditional residential communities in the city center. In neighborhoods such as Bunker Hill, West Adams, and Hollywood, mansions were subdivided into rooming houses, and environmental quality suffered.

By the 1980’s and 90’s, however, a reverse trend became visible; as Westside real estate prices became stratospheric, young families and creative professionals sought out affordable space in diverse and lively communities such as Hollywood, Silverlake, Echo Park and Mount Washington. With them came an infrastructure of coffee shops, restaurants, shopping and entertainment, turning previously blighted neighborhoods into lively, multi-cultural, and youthful communities with easy access to the downtown arts and entertainment scene.

The 405 freeway had been approved in 1955 to accommodate the booming population, with little thought that by the early 21st century it would come to represent a great divide. Since then it has become the busiest and most congested freeway in the United States.

For those of us who live west of the great divide, by early afternoon until shortly after 7pm we are denied an easy access to the east; there is no traversing the city in a timely manner. This means that those who are east of the 405 are literally cut off from downtown cultural activities. Some efforts have been made to bring performance spaces, galleries, and museums to the tony Westside, but they will always lack the historical layering and cultural complexity of the affordable city center.

Lacking a cultural center on the Westside and denied access to the livelier areas on the Eastside, has forced Westsiders into a more insular lifestyle; the single family home has become the source of entertainment. In the last decade, the proliferation of estates with gourmet kitchens, screening rooms, pools, spas, and vast areas for entertainment, has changed the character of many communities.

The lack of affordable workforce housing on the Westside, and the economic success of Santa Monica has meant that a small army of staff and workers commutes daily from the Eastside and the Valley, and flees for home in the early afternoon, clogging all arteries leading to the 10 and 405 freeways. Until there is a public transport system and more affordable housing on the Westside, there appears to be no hope of joining back the East and West sides of Los Angeles.

The Korman Residence by Cory Buckner Architects

Contemporist

Click here to read original story.

In 2005, Dr. Jeremy and Ann Korman commissioned Cory Buckner, Architect to design a remodel to their Brentwood home. With two daughters and a French bulldog, named ZsaZsa, they had long outgrown their 1700 square foot ranch house built in the 50s. They longed for contemporary, comfortable space for their family.

In 2005, Dr. Jeremy and Ann Korman commissioned Cory Buckner, Architect to design a remodel to their Brentwood home. With two daughters and a French bulldog, named ZsaZsa, they had long outgrown their 1700 square foot ranch house built in the 50s. They longed for contemporary, comfortable space for their family.

The program for the project included a second story addition to house a master suite, a home office for Dr. Korman, a surgeon, and a painting studio for Ann. Situated at the bottom of a canyon, the entrance to the original house was 66 steps from the street to the front door. The new design incorporated a bridge to an entrance at the second floor addition reducing the steps to 44. The former master bedroom on the lower level became one daughter’s room and two small bedrooms at the rear of the house were combined to make a suite for the other daughter.

The entire house was impacted by the remodel with most of the house being demolished. The former master suite, kitchen, and dining roof structure remained intact but many interior walls were demolished or reconfigured.

The entire house was impacted by the remodel with most of the house being demolished. The former master suite, kitchen, and dining roof structure remained intact but many interior walls were demolished or reconfigured.

Ann was drawn to the postwar post and beam architecture of the modernist era and selected Buckner who specializes in mid-century modernist architecture remodels and restoration. The house is located just outside of Crestwood Hills, formerly called the Mutual Housing Association tract, designed by A. Quincy Jones, Whitney R. Smith, and Edgardo Contini in the late 40s. Buckner has restored or remodeled more than a dozen houses in the neighborhood and is author of A. Quincy Jones published by Phaidon Press.

Because the house is set at the bottom of a canyon it was important to capture as much light as possible. Buckner designed a butterfly roof structure for the second story addition in order to capture light from high clerestory windows that reach up to the ceiling. Some of the window configurations on the original house incorporated posts and worked well with the second story addition designed as an exposed post and beam structure. Skylights were added in the kitchen and over the fireplace, which in addition to adding light in the living room accents an articulated tiled fireplace mass. All bedrooms face patios or decks with sliding glass doors that dissolve the boundary of indoor and outdoor space.

The finish material palette was kept appropriate for a house tucked into a wooded canyon. The existing house was finished in rough sawn board-and-batt with a composition shingle roof. The new house is clad in new growth cedar tongue and groove siding with a roof covered in slate green gravel. Douglas fir flooring and cabinets were used throughout the project. The countertops are Ceasarstone, tile is either recycled tiles from ModernArc or glass tiles from Ann Sachs.

The finish material palette was kept appropriate for a house tucked into a wooded canyon. The existing house was finished in rough sawn board-and-batt with a composition shingle roof. The new house is clad in new growth cedar tongue and groove siding with a roof covered in slate green gravel. Douglas fir flooring and cabinets were used throughout the project. The countertops are Ceasarstone, tile is either recycled tiles from ModernArc or glass tiles from Ann Sachs.

Shortly before demolition began, Ann sold or gave away all of their furniture with the idea of purchasing all new furniture for the project. As the daughter of an art collector, she has an exquisite eye for design. She worked closely with the architect in selecting every piece of furniture and finishes. To start the collection on the right foot, at the beginning of the project, her father gave her a George Nakashima dining table and coffee table.

Pro Portfolio: Cory Buckner’s Brentwood Modern

Los Angeles Times

Design, Architecture, Gardens,

Southern California Living

(September 5, 2011)

Cory Buckner Architects recently finished a Brentwood residence designed to make the most of its natural surroundings. It’s the latest installment of Pro Portfolio, our feature posted every Monday in which we look at a recently built, remodeled or redecorated home with commentary from the designer.

Cory Buckner Architects recently finished a Brentwood residence designed to make the most of its natural surroundings. It’s the latest installment of Pro Portfolio, our feature posted every Monday in which we look at a recently built, remodeled or redecorated home with commentary from the designer.

Project: Demolish a nondescript 1,900-square-foot house and build a 4,000-square-foot residence for a family of four, plus a 1,400-square-foot artist’s studio.

Location: Brentwood.

Architect: Cory Buckner Architects. General contractor: Palisades Construction, principal David Stumfall and supervisor Randy Hayden, (310) 454-5728.

Architect’s description: This property is situated in the well-known postwar architectural community of Crestwood Hills, designed by architects A. Quincy Jones, Whitney R. Smith and structural engineer Edgardo Contini. The site had been occupied by a two-story house untouched since the late 1950s with breathtaking views of the Santa Monica Bay and city lights.

With just the top 6 feet of the new house visible at street level, the Brentwood residence appears as a modest statement among the neighboring postwar Modernist homes. Stepping down the hill, the house blends in with neighboring houses and affords each level of the house breathtaking views of the Bay.

With just the top 6 feet of the new house visible at street level, the Brentwood residence appears as a modest statement among the neighboring postwar Modernist homes. Stepping down the hill, the house blends in with neighboring houses and affords each level of the house breathtaking views of the Bay.

Exposed natural materials, large expanses of glass dissolving the boundary of indoor and outdoor space and

a butterfly roof address the Modernist architecture of the surrounding community.

With the primary view and exposure to the south, the use of passive solar devices such as appropriately sized roof overhangs minimize the sun’s effect in the summer and maximize heat gain in the winter. Operable windows and doors on the lower floors capture funnel ocean breezes, with air circulation also helped by clerestory windows at the top of the house.

Lady of the Canyon

Lady of the Canyon

Text: Michelle Gringeri-Brown

Photography: George Pesce & Briand Guzman

Zander Lichstein bought his 1957 house from the second owners in 2001, Located in Santa Monica Canyon, by 2006 he and his wife, Morina, were debating adding on versus moving to a larger place, but they loved their neighborhood and the midcentury details of the 1 ,860-square-foot home.

The couple met with several architects and even hired one before deciding it just wasn’t the right fit. Second up to bat was Cory Buckner. “[The first architect] did not under-stand the driving elements we loved about our midcentury home, such as maximizing views and privacy, the warmth of the natural beam construction and catching the ocean breeze here in the canyon,” says Morina. “We were certain Cory was the right architect to work with when she climbed our hill and our rooftop, observed the wind and the sun’s path, and appreciated the design elements we enjoyed about our home.”

“We had seen Cory’s work in a few publications and assumed that she would be out of our budget,” adds Zander. “However, at our first meeting, it was obvious that she understood exactly what we valued in our original home, and exactly how to make the expansion fulfill our dreams for the house. She also struck us as very practical, experienced and easy to communicate with. Cory returned a few days later with sketches and a scale model that totally nailed it. The final plans are nearly indistinguishable from that first proposal it was that spot-on.”

Buckner has serious roots in midcentury architecture. In addition to new construction emblematic of the era, and high-end renovations like Courteney Cox’s $20 million A. Quincy Jones home in Beverly Hills, she wrote the book-literally-on Jones in 2002. And her interest wasn’t just professional: after losing their 1961 modem home in Malibu to a brush fire, in 1993 Buckner and family moved to a midcentury home designed by Jones, Whitney R. Smith and Edgardo Contini in Brentwood’s Crestwood Hills.

“Of the 350 homes in our neighborhood, only 31 houses remain of the original 160 designed by the joint venture known as the Mutual Housing Association,” Buckner explains. “We restored the house and tried to establish an HPOZ (Historic Preservation Overlay Zone) in our area, but were unsuccessful since we did not have the backing of two-thirds of the community.

“In an effort to save the few remaining MHA houses, I submitted ours and four others for monument status with the City of Los Angeles. After a great deal of persuading, we were granted historic status for four of the five. Every few years after that first submittal, I would gather together applications for another four houses until we had close to half declared historic. Recently, individual homeowners have submitted their own houses and we now have more than half of the remaining structures declared Historic Monuments with the city.”

The Lichsteins’ home had two bedrooms, one of which they use as an office, and a single bath, but they wanted more room for a future family. Buckner’s proposal called for a master suite, two bedrooms and two more baths in a butterfly roofed second story, as well as a playroom on the ground floor. The existing kitchen was remodeled and a wall removed to open it to the living and dining rooms. The back bedroom was turned into a family room with accordion doors that can close it off from the living room or the play area. Radiant heating was installed throughout and a new fireplace and built-in seating added to the living room.

“We had spent many years conceptualizing how [an addition] could be done-stair placement, rooflines, etc.,” recalls Zander. “Before we started the process, I had sketched every roofline that I could imagine integrating with the existing pitches. Cory’s butterfly solution, and the rearrangement of the first floor, were both surprises and brilliant solutions to the problems that we tried to solve on our own.”

“We had spent many years conceptualizing how [an addition] could be done-stair placement, rooflines, etc.,” recalls Zander. “Before we started the process, I had sketched every roofline that I could imagine integrating with the existing pitches. Cory’s butterfly solution, and the rearrangement of the first floor, were both surprises and brilliant solutions to the problems that we tried to solve on our own.”

“The basic structure of the addition was designed to echo the midcentury structural system of exposed beams and 1″ x 6″ tongue-and-groove ceilings,” Buckner says. “Clerestory windows and a butterfly roof further give a nod to the original character of the house. Because it is set against a hillside, it was important to capture as much light as possible.”

The couple chose the finish materials, making sample boards and sharing them with Buckner in what Morina calls “disaster check” meetings. “Cory sent us to Ann Sacks, where we found the subway tile used in the guest and children’s baths, as well as the l’ x 2′ floor tiles we had loved at another home she worked on. One thing Cory absolutely drove was the selection of the neutral subway tile in our kitchen. We had fallen in love with a wonderful retro orange/red/lime glass backsplash tile that would have ruined the room, and she knew it and kindly steered us back to safer ground. We love our kitchen now, thanks to her help.

“On the baseboards, Cory actually suggested a modern solution of a simple reveal versus a traditional molding. We wish we took her advice, but at the time thought it might look too minimal not to have a baseboard.”

The project took two years, almost double the predicted time, the Lichsteins say. During that period, they went through two contractors, had several vendor issues and put things on hold when their son, Oliver, arrived early and spent five months in NICU.

“The biggest challenge to the project was meeting the city’s requirements for remodels that exceed 50-percent added footage,” Buckner explains. “Since the original house was so small to begin with, it was impossible to avoid falling under those restrictive requirements. A great deal of time and engineering was needed to prove [the integrity of existing foundations, as well as adding new foundations and two-story retaining walls to meet current code and support the hillside beyond.”

“Everyone says that construction estimates of time and money should

be doubled,” relates Zander. “It was true [in our case] and that was a challenge. But the biggest surprise was how difficult each decision point is, and the level of detail each step can involve when you are working with a contractor on a time and materials basis. For example, the precise layout of tile to minimize odd joints required foresight and planning all the way back to the framing stages.”

“The extent of the demolition and shoring up of our existing home was shocking to us; nearly every wall was torn down to the studs,” adds Morina. “The office and its accompanying bath-room downstairs were the least touched by construction, but even there we replaced a closet with a Murphy bed and file cabinets, and added an egress window. In addition, that bathroom’s beautiful yellow and grey ’50s tile work was damaged by the demolition on the opposite side of the wall. [Fortunately], our amazing original wood beam living room and office ceilings only need a teeny touchup after construction.”

“Now that we are all done and in our refreshed midcentury home … on the lot and in the neighborhood we love, it might have all been worth it,” muses Zander. “We love the home Cory designed for us and with us. A testament to her design is that most visitors have a hard time identifying which areas of our house were part of the addition. In an era of monster lot-fillers, I think every one of our neighbors has told us how delighted they were with the seamless look and matched scale that we achieved.”